Imants Barušs

In my background research for writing a book about death from a scientific perspective—including discussions about deathbed phenomena, after-death communication, mediumship, instrumental transcommunication, anomalous physical phenomena such as poltergeist activity and possession, neardeath experiences, past-life experiences, and the nature of the afterlife—there are several things that I have noticed that I think are important to point out.

At the outset, I want to note the volume of books that are available from trade book publishers asserting the existence of life after death. So, for instance, there are books written by someone who has had a near-death experience, or someone whose deceased son appears to be communicating through a medium, or someone who ostensibly talks to the dead by recording the noise from radios tuned between stations. Often the authors have been thrust into these situations without having sought them out. And, usually, although not always, they are unaware of the relevant academic literature and have no training in research design nor the interpretation of empirical data. Of course, that is not their fault. Their experiences were never part of a scientific inquiry but, in some cases, were subsequently reconceptualized as evidence for life after death. And so, there are bound to be problems. In particular, what I have noticed, is that non-experts frequently assume that the occurrence of any anomalous event, such as a medium providing correct information or a radio that is still working in spite of having had its vacuum tubes removed, is prima facie evidence for the persistence of the personality after the death of the physical body. Of course, that is not a logical inference.

The problem is compounded by the fact that academics, with a few exceptions, have simply avoided this subject matter. That is not surprising. The academy is still predominantly saturated with materialist ideology, whereby survival of death is regarded as being impossible. So there is no point to survival research. Here are three skeptical arguments: (1) It has been argued that those who are sympathetic to the possibility of survival should not be doing survival research because they are biased in favor of survival. (2) There is a correspondence between specific neural networks and human behavior. As the underlying physiological substrate is damaged, such as in dementia, the cognitive abilities subsumed by that substrate are lost. Therefore, consciousness is dependent on the proper functioning of the brain and cannot survive the deterioration of the brain. (3) For near-death experiences with temporal anchors, whereby experiencers correctly identify events that occurred at a time when their brains were not functioning in the manner that is necessary for such perception, the skeptical explanation is that the brain functions in mysterious ways that have yet to be discovered.

What is wrong with these arguments? Well, (1) true believers in materialism could also be biased and, in fact, sometimes state their purpose as that of reifying anomalous phenomena in conventional terms; (2) correlation does not imply causation; and (3) speculating that mysterious abilities of the brain will be found to explain anomalous perception is just promissory materialism and directly contradicts the neuroscientistic thesis that the appropriate functioning of known neural correlates is required for the production of subjective experience, which was the argument for the cessation of consciousness with physical death in the first place. With few exceptions, I find arguments by self-identified skeptics to be logically flawed and superficial, so they end up not being useful.

This discussion about skepticism opens up the theoretical question: How are we to understand poltergeists, past lives, the sense of presence, and so on? I find there are three main positions, which I refer to as materialist, living agent psi

(LAP), and survival. The materialist explanation is an explanation in conventional terms, such as those endorsed by many self-identified skeptics. In other words, we have misperceptions, misrememberings, errors in documentation, cognitive or psychosocial nonconscious processes, mental illness, fraud, and so on as explanations of phenomena. For instance, hearing snippets of voices in the static created by radios tuned between stations is probably just pareidolia, the psychological tendency to find meaningful structure in ambiguous stimuli. LAP, previously known as super-psi, attributes phenomena of interest to remote viewing and remote influencing by experiencers. For instance, a medium gets correct information about someone who is deceased. Is this just a medium with good remote viewing skills, able to extract that information from wherever it can be found? Survival refers to the survival of consciousness after death. There is usually an added assumption that any such surviving disembodied consciousness has the same constitution as the embodied consciousness, for instance, by retaining a person’s memories, sense of identity, motivations, and so on. So, someone who was interested in playing hockey while alive remembers after death that they were playing hockey and continues to have such an interest. That assumption is usually just implicitly held without critical examination.

We can think of materialism, LAP, and survival as consecutive positions clockwise from left to right on a dial. Given the data that we have from the various phenomena, how far can we move the dial clockwise, toward survival? To give some idea of the difficulty that we run into, we can consider a modern version of Plato’s analogy of the cave from The Republic. Suppose that we live in a room with a television set. We have never been out of the room. We are watching a hockey game on the television set. Because we have never been outside the room, we are convinced that the hockey game is in the television set. We can prove this by removing a resistor and a diode here and there and watching the image on the monitor degrade. We can put a disc of a hockey game into our disc player and thereby prove that there does not even need to be an outside world. We can identify the activity of the electronic circuits in the television that correspond to taking a shot on net, and so on. Clearly the television is the source of the hockey game. Of course, it is not. There really is a hockey game being played outside the room, but we have no way of proving that. For every permutation of the image, we can speculate about a way in which the television set itself created that. That is what we are up against. We are alive. We are not dead. That presents an epistemological problem. All of our evidence is evidence within the domain of the living, not the domain of the deceased, whatever that might be, yet we want to use it as evidence of activity among the deceased. But we can always come up with speculative ways to explain what is happening by reference to the living.

If we proceed as scientists, then what are we doing? We are evaluating theories against the evidence for them. A theory is unconstrained if there is insufficient evidence to favor one theory over another. When a boy dreams about an airplane crash, is that the result of a previous life time in which he crashed in an airplane or because of the video about airplanes that he watched over and over again (Sudduth, 2021)? In a way, science is an inherently contrived activity. We need to find circumstances in which conditions are such that we can test the differences between our theories. Or, better, yet, we want to have control over the relevant variables ourselves and create circumstances in which we can tease apart the different theories. This is the point of the Large Hadron Collider for testing theories of subatomic physics, for example.

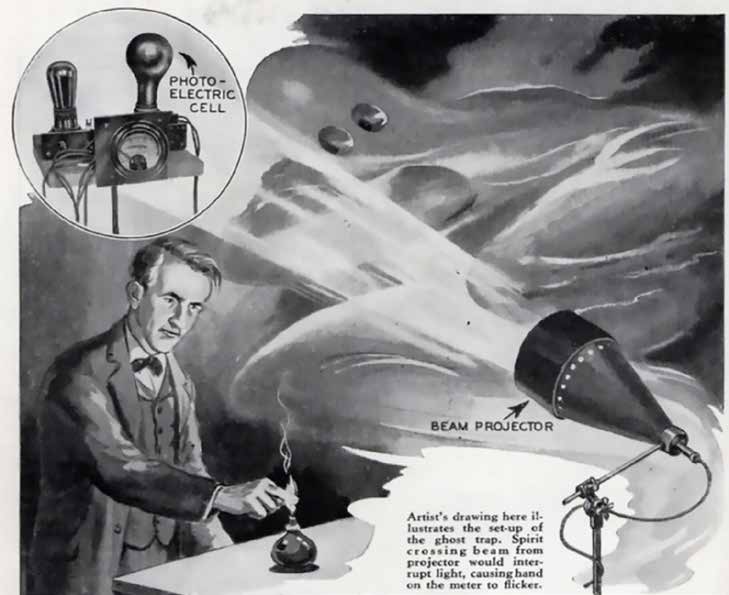

How does that translate to the context of death? How about inviting spirits to insert themselves into a light beam directed at a photoelectric cell, as Thomas Edison did (Edison’s own secret spirit experiments, 1933), or requesting spirits to bring their “hands” up to the sides of a box containing a plasma globe, to affect the plasma filaments inside it, as Gary Schwartz has done in his research at the University of Arizona (Schwartz, 2021). Alas, when it comes to death, experiments are rare. What we have instead are stories. We can relabel those stories as “case studies” or “field investigations,” but that is not going to please those who demand to see laboratory experiments before they are willing to accept any new information. But here is something important about science. Science is relentless in the pursuit of truth and will proceed with whatever techniques are available to advance understanding, however imperfect they might be. So, we have stories. Do we have stories with good documentation about events in naturally occurring “contrived” circumstances so that we can discriminate between theories and move our scientific exploration forward?

The answer is yes. I think that the stories about so-called veridical near-death experiences can distinguish between explanations and move the dial to the right. For instance, in a case discussed by cardiac surgeon Lloyd Rudy Jr., Rudy’s patient was pronounced dead during cardiac surgery. The cardiac surgeons left the operating theatre to inform the man’s wife. They returned later and stood in a doorway with arms folded discussing the case. Somebody had forgotten to turn off the heart monitors, so there was paper piling up on the floor. After some 20 to 25 minutes without a pulse and, hence, no brain activity sufficient to support consciousness, the surgeons noticed a promising signal in the paper record that became a heartbeat and resuscitated their patient. Upon recovery several days later, the patient apparently correctly described the appearance of the operating theatre and events that had occurred at the time he was supposed to be dead, including the perception of the surgeons standing in the doorway with their arms crossed (Barušs & Mossbridge, 2017).

First, this is a situation that the experiencers had not anticipated. This was not a prospective, scientific study. Such studies have been attempted by setting targets near the ceiling in hospital rooms for patients to look at while they are having a near-death experience but, to date, no one has reported perceiving any of those deliberate targets. What we have are memories of what a patient said and memories of what the conditions were in the operating theatre that he was ostensibly describing. These are memories by two cardiac surgeons who agree about the details as described here. Second, we have ostensibly veridical perception by a patient lying on an operating table. This moves the dial toward LAP. Third, we have something more. The image of the two cardiac surgeons standing with arms folded in a doorway is a temporal anchor. It sets the timing of the patient’s remote viewing to the period when there was no heart activity and, hence, no brain activity of the sort that is required for perceptual experiences. The implication is that the patient was able to “see” without a functioning brain. And, if so, then what exactly is the nature of the consciousness that does that seeing? Can we move the needle toward survival?

There is something else that we need to take into account. The accuracy of remote viewing appears not to fall off with temporal displacement, so the veridical perception in this case need not have taken place at the time that the patient was in the operating theatre, but could have occurred upon subsequent recovery when the brain was working again. In fact, those who have had a near-death experience frequently have anomalous abilities turned on by the near-death experience, including precognition, the “Pauli effect,” whereby mechanical devices fail in their presence, and the “reverse Pauli effect,” which appears to give experiencers the ability to heal other people, electronic devices, and so on. We have no information about whether this patient’s anomalous abilities were turned on by the near-death experience and, if so, whether he made the observations in the operating theatre using retrocognition, but ascribed them to the time of their occurrence. It is a possibility.

Anomalous events such as these can be denied, not because of the quality of the evidence, but because they exceed a reader’s boggle threshold. Another significant theme, which can be challenging, is the extent to which physical stuff moves around by itself. I mean macro-pk. Bells that ring by themselves. Mist from a vaporizer that takes the shapes of recognizable faces. Computers that display meaningful words by themselves. Dead radios that start playing music. A radio with its vacuum tubes removed that continues to broadcast recognizable speech. Flowers at a funeral that leave their container and smash to the floor. A book that disappears and then, after an extensive search, reappears in the place where it was supposed to be in the first place. Stones flying through the air around corners. A woman sitting in a chair who has levitated and who witnesses are hard-pressed to push back to the chair. A crystal that dematerializes when investigators try to pick it up. Oh, and micro-PK: a random event generator that deviates from random behavior when “being 7” is being channeled by a medium. Such suspension of Newton’s laws of motion is so prevalent in all aspects of the phenomena associated with death that it needs to be carefully considered.

This does raise another issue in trying to move from LAP to survival. The idea is that some of the anomalous violations of Newton’s laws are the result of interference by discarnate entities. But how are they going to exercise their influence? It would seem that is going to be through the same mechanisms as LAP, namely, remote viewing and influencing. So the question can be reframed from LAP or survival to LAP by whom? Who is the agent? Is the agent alive or dead? Is it LAP or DAP, dead agent psi? To give another example: Suppose someone were to come to me and start describing poltergeist phenomena. I might ask whether when she comes home from school, the lipstick on the top of her dresser has been nicely lined up in a row while she was gone. Yes, she says. The point is that frequently there appears to be agency with some degree of intelligence that is manipulating the physical stuff. In the computer text case, it appeared to be a student’s grandmother writing meaningful messages to her family (Barušs, 2013). For Schwartz, it is an “I’m Not a Robot” task to which answers are given by unseen entities by bringing their “hands” up to the sides of his box. The point of using the “I’m Not a Robot” task is precisely to determine whether the dead agents are intelligent.

So, where does the dial end up? What I have noticed is that it is not so much the impact of explicit arguments that I am making for one theory in preference to another that is convincing, but that, upon writing story after story, there is a slowly dawning realization that the room with the hockey game is simply too small to encompass all of the phenomena that we need to accommodate. We are asking so much of our available living agents that there is no way that they can be the source of all of the anomalies. This is a variation on philosopher Stephen Braude’s argument from crippling complexity to prefer survival to LAP (Braude, 2003). It becomes clear that physical manifestation is just a thin veneer of a much greater reality that is psychological in nature. And that unseen, greater, psychological reality keeps stirring the physical veneer (Barušs, 2021). Note that we have privileged the left side of the dial over the right side, and have seen whether the dial can move clockwise from materialism to survival. Conversely, had we privileged the right side of the dial in our investigation, then perhaps the dial would never have had reason to move counterclockwise toward materialism at all and we would simply have accepted survival. In either case, the idea that presents itself is that all that death does is release the mesmerizing hold of the physical veneer on the consciousness of the psyche so that it can drift into the greater reality that lies underneath.

Acknowledgements

I thank Monika Mandoki and Karalee Kothe for critical feedback about this paper. I thank Shannon Foskett, my research assistant, for critical feedback, editorial assistance, and proofreading in the preparation of this paper. And I thank King’s University College for a paid sabbatical leave and for an internal research grant that has given me the opportunity and resources to write a book about death.

IMANTS BARUŠS has a MSc in mathematics and PhD in psychology and is a professor in the Department of Psychology at King’s University College at Western University where he teaches courses about consciousness and altered states of consciousness. He is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Scientific Exploration, a Consulting Editor for Psychology of Consciousness, and one of the founders of the Society for Consciousness Studies and their journal Consciousness: Ideas and Research for the Twenty First Century. He has authored or co-authored more than 100 presentations, 55 papers, and 7 books, including Alterations of Consciousness and Radical Transformation: The Unexpected Interplay of Consciousness and Reality.

REFERENCES

Barušs, I. (2013). The Impossible Happens: A Scientist’s Personal Discovery of the Extraordinary Nature of Reality. Alresford, Hampshire, UK: John Hunt Publishing.

Barušs, I. (2021). Radical Transformation: The Unexpected Interplay of Consciousness and Reality. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic.

Barušs, I. & Mossbridge, J. (2017). Transcendent Mind: Rethinking the Science of Consciousness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Braude, S. E. (2003). Immortal Remains: The Evidence for Life After Death. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

“Edison’s Own Secret Spirit Experiments” (1933). Modern Mechanix and Inventions, October, pp. 34–36.

Schwartz, G. E. (2021). “A computer-automated, multi-center, multi-blinded, randomized control trial evaluating hypothesized spirit presence and communication,” Explore, 17, 351–359.

Sudduth, M. (2021). “The James Leininger Case Re-examined,” Journal of Scientific Exploration, 35(4), 933–1026.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.