Eric Wargo

“My people are free!” “My people are free!” She came down to breakfast singing the words in a sort of ecstasy. She could not eat. The dream or vision filled her whole soul, and physical needs were forgotten.

Mr. Garnet said to her: “Oh, Harriet! Harriet! You’ve come to torment us before the time; do cease this noise! My grandchildren may see the day of the emancipation of our people, but you and I will never see it.”

“I tell you, sir, you’ll see it, and you’ll see it soon. My people are free! My people are free.”

When, three years later, President Lincoln’s proclamation of emancipation was given forth, and there was a great jubilee among the friends of the slaves, Harriet was continually asked, “Why do you not join with the rest in their rejoicing!”

“Oh,” she answered, “I had my jubilee three years ago. I rejoiced all I could then; I can’t rejoice no more.”1

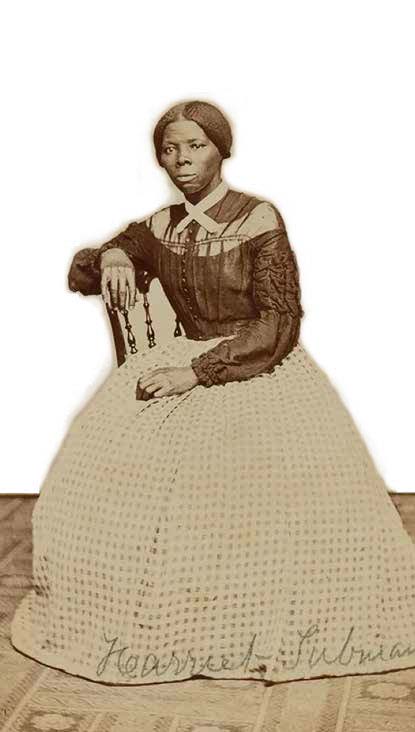

Harriet Tubman’s achievements—liberating large numbers of slaves from Maryland farms and then helping lead Union forces in a major action during the Civil War—earned her a central place in the story of the struggle against slavery in America. After the war, she became a suffrage activist and tirelessly supported poor Black people in Auburn, New York, using funds from her public speaking and donations. Ever since, she has been a beacon for Black Americans and feminists—almost the perfect icon and figurehead for multiple intersecting identities and struggles against oppression.

I say “almost” because there’s that nagging biographical detail, which Tubman’s abolitionist friends and contemporaries struggled to assimilate within the larger picture of this complex woman, and which most historians since then have either rejected outright or minimized: her propensity to have what we would now call precognitive dreams and visions, as well as her claims to have been frequently guided to safety by the voice of God.

Tubman never learned to read or write, so despite years describing her exploits to lecture audiences after the Civil War—she was a brilliant and witty storyteller, by all accounts—we today are limited to hearing her story mediated by others.2 It presents difficulties trying to extract the “actual, historical” Harriet Tubman from the various religious, scientific, racial, and political biases of her biographers, not to mention the onion-like layers of hagiography and mythmaking that have grown up around her.3

As a conductor on the Underground Railroad, Tubman earned the appellation “Moses,” but there was as much or even more of Joan of Arc in the dreaming and gun-toting freedom fighter. Because so many children’s stories about Tubman play up that comparison, serious biographers have had a hard time believing the supernormal aspects of Tubman’s story, assuming that her dreams and talking to God must simply be parts of the myth, or at best symptomatic of slave superstition or even brain disorder. But I will argue in what follows that, despite their anecdotal nature—with history and biography, we’re inevitably in the realm of anecdote—the abundant claims made independently by Tubman’s many abolitionist associates, friends, and early biographers add up to a picture that historians of the supernormal should not ignore. Tubman does seem to have regularly experienced precognition both in dreams and in her waking life, even if she herself used a religious idiom to describe and explain those experiences. Her story is consistent with what has been reported by other, better-studied psychic individuals in more recent times, including military remote viewers and contemporary precognitive dreamers.

Tubman’s Origins and Anti-Slavery Career

Tubman was born Araminta (“Minty”) Ross, probably in early 1822, on a plantation in Dorchester County, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, owned by a prominent local landowner named Anthony Thompson.4 Her father, Ben Ross, was the property of Thompson, but her mother, Harriet “Rit” Green, wasowned by Thompson’s stepson, Edward Brodess. When she was one or two, Minty Ross along with her four older siblings and mother were taken away from their father and brought to Brodess’s plantation 10 miles away in Bucktown (also in Dorchester County). By law, the young Ross belonged to Brodess, but he frequently hired her out to other whites in the area, a common practice. Separation from her mother and siblings during these long stretches away from the Brodess plantation was itself painful, and adding to the suffering, some of these temporary masters were quite cruel. Two of the defining traumas of her childhood, potentially relevant to the expression of her psychic abilities, occurred during these stints.

Probably around age 7 or 8, Ross was hired out to a married woman, “Miss Susan,” to work as a maid and nurse for her newborn. Miss Susan was sociopathically abusive, even by slavemaster standards—brutally whipping the child on her first day of work for not knowing how to dust furniture, and so on. The mistreatment appalled even Susan’s visiting sister, who insisted Susan stop hurting her. The detail that is potentially relevant to the psychic story I’ll be telling is that Miss Susan made her young slave stay awake, long into the night, every night, to rock the cradle of her “cross, sick child” to keep it from crying. We’ll see later why this could be important.

The episode that has received more attention from biographers is a severe head injury Ross received probably in her very early teens, after having been hired out to break flax for “the worst man in the neighborhood.” While she was on an errand to a dry-goods store for this temporary master, an overseer from a neighboring farm commanded Ross to help restrain one of his slaves who had fled and taken refuge inside. Ross refused, and the overseer hurled a two-pound scale weight at the fleeing man, which fell short and hit her instead, breaking her skull. Ross was given no medical care and was made to return to work after a day in bed, but she kept fainting, and blood and sweat running into her eyes made it impossible to see. Her temporary master returned her to Brodess as worthless, and Brodess was unable to sell her thereafter because of her injury.

Ross experienced frequent headaches the rest of her life as a consequence of her head injury. She also suffered extreme lethargy and a tendency to fall spontaneously into deep, nonrestful slumber. Biographer Kate Clifford Larson argues that her narcoleptic episodes as well as her lifelong religiosity and belief in the reality of her frequent dreams and visions were results of temporal lobe epilepsy precipitated by the injury—a plausible but also problematic assumption that I will also consider later.

Ross took the name Harriet Tubman in 1844, at age 22, when she married a free Black man named John Tubman. She remained the property of Brodess until the farm passed to his wife upon his death in March 1849—a death Tubman had started explicitly praying for just a little over a week before it happened. There was growing fear among the slaves that, despite promises to the contrary, some of them would be sold away into far worse conditions on the malarial rice plantations farther to the south, where any escape to freedom was less imaginable. Beset by persistent dreams of horsemen and the terrified screams of women and children, Harriet talked much of escape, even though her husband ridiculed and belittled her aspirations. There is no indication that these dreams were a specific premonitory warning or that it was a dream that finally prompted her escape. It was after learning (in the usual way) that two of her sisters had been sold away on a chain-gang, and fearing that she was next, that she finally made her decision to escape in autumn of that year.

Tubman made an initial abortive attempt with two of her brothers, but they changed their minds and wouldn’t continue, so she made her second, successful attempt alone. The Underground Railroad was already a well-functioning secret network at that point, made up of free Blacks, slaves, Quakers, and other anti-slavery whites, as well as white people simply willing to shelter escaped slaves in exchange for payment. (By the late 1840s, hundreds of slaves escaped from the Eastern Shore each year, prompting slaveowners’ increased vigilance.) Aided by a local white woman to whom she gave her favorite bed quilt in exchange for her help, and following the North Star as her compass, Tubman made her way to the safe haven of Philadelphia in autumn of 1849. Having spent nearly three decades enslaved, crossing the Pennsylvania state line was like being reborn: “I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person,” she later recalled to Sarah H. Bradford, one of her early biographers. “There was such a glory over every thing; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”5

Over the following decade, Tubman made multiple stealthy trips back to the Eastern Shore—including back to the farm she had fled from—to bring her family members and many other slaves to freedom.6 These adventures have been widely told, often with embellishment, in children’s books. Popular accounts based on Bradford’s writings often claim that Tubman freed 300 slaves on 19 such missions, but historians now agree that Bradford’s figures are inflated. The truth is still impressive: Larson’s careful research points to 13 separate missions and approximately 70 slaves directly led to freedom by Tubman, who also left instructions for many more to make their own way north, in what became a “stampede” of fugitives by the late 1850s.7 The Fugitive Slave Act, which legally obligated Northerners to return escaped slaves to their Southern masters, was passed in 1850, and although widely resented and often ignored, it made life for escaped slaves perilous even in Northern states. So Tubman’s missions carried her and her companions from Maryland to Ontario, in Canada, enlisting the aid of a wide network of abolitionists and fellow Underground Railroad conductors all along the way.

Harper’s Weekly

Tubman’s skill moving secretly through dangerous enemy territory, utilizing disguise and trickery to evade detection, made her a legend among Maryland slaves—who called the mysterious (and, many assumed, male) liberator Moses. Her disguises were varied, including dressing as a man, but one of her favorite tactics was hiding in plain sight, pretending to be an old or confused woman. On one of her missions, she avoided the gaze of her former master by making a deliberate commotion with some chickens she was holding. Effectively she cloaked herself within the prejudices of her enemies, who never imagined a Black woman going about her daily business could pose a threat.8 On another occasion she approached and essentially flirted with some Irish laborers working on a Delaware bridge that her large party needed to cross. She struck up a conversation and intimated to them that she was looking for a white man to marry, successfully distracting the fellows long enough that her fugitives could slip by unnoticed. Although her missions were perilous and there was a price on her own head as well as those of many of her charges, she was fond of boasting that she “never lost a passenger.”

Tubman’s skills and experience using secret slave communications networks also made her a valuable asset in larger antislavery actions that were planned. In 1858, militant white abolitionist John Brown sought Tubman’s aid in planning his raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now, West Virginia), which was intended to foment a slave uprising in that state. Then in April 1859, Tubman helped antislavery activists in Troy, New York, stage a daring rescue of a fugitive slave, Charles Nalle, from U.S. Marshalls. She began by infiltrating the U.S. commissioner’s office where Nalle’s fate was being contested by lawyers, in the guise of “a somewhat antiquated colored woman” (as the local newspaper reported) wearing a conspicuous sun bonnet. She sat unnoticed amid the proceedings and then, when the authorities decided to move Nalle to a more secure nearby courthouse, she signaled the mob outside and then led them in prying Nalle from the grip of authorities and conveying him to a waiting ferry on a nearby waterfront.

The climax of Tubman’s anti-slavery career came at the beginning of June 1863, when after an initial scouting mission to gather intelligence on enemy locations, she helped Union Colonel James Montgomery (a former compatriot of John Brown’s) lead a force of Union soldiers up the Combahee River in South Carolina, routing Confederate forces, setting plantations and storehouses ablaze, and liberating more than 700 slaves. She is widely claimed to be the first woman to lead U.S. troops in a Civil War battle.9

“Omens, Dreams, and Warnings”

The first person to tell Tubman’s story in print and “out” her as the legendary Moses who had struck so many blows against Southern slaveowners was Boston schoolteacher and journalist Franklin Sanborn. Sanborn first met Tubman in 1858 via the network of abolitionists who were secretly funding Brown’s planned raid, and Tubman came to trust the writer as a genuine ally in the anti-slavery cause. Telling the rudiments of her story in 1863 in the antislavery newspaper he edited, The Boston Commonwealth, Sanborn paints a compelling picture of a cunning tactician and fearless fighter in the cause of civil rights. He also admired her spy-like caution, for instance her practice of carefully quizzing strangers (including Sanborn, on their first meeting) with daguerrotypes of mutual abolitionist friends, to ensure her visitors were who they claimed to be.10

In his article, Sanborn described Tubman as “the most shrewd and practical person in the world, yet she is a firm believer in omens, dreams, and warnings.”11 Pay attention to that “yet.” The journalist had difficulty reconciling Tubman’s paramilitary prowess with her interesting but hard-to-explain inner life, and this difficulty is a theme running through pretty much everything that has been written about Tubman since. Then as now, the sciences were ascendant among many educated persons like Sanborn, and with that came inherent skepticism at claims of miracles and the supernatural. Yet, despite sympathy with readers’ inevitable doubts, Sanborn felt strongly that this “singular trait”12 in Tubman’s character was too important to be ignored.

For example, Sanborn described Tubman’s flying dreams that may have been what we now call out-of-body experiences:

She declares that before her escape from slavery, she used to dream of flying over fields and towns, and rivers and mountains, looking down upon them “like a bird,” and reaching at last a great fence, or sometimes a river, over which she would try to fly, “but it appeared like I wouldn’t have the strength, and just as I was sinking down, there would be ladies all dressed in white over there, and they would put out their arms and pull me across.” There is nothing strange in this, perhaps, but she declares that when she came North she remembered these very places as those she had seen in her dreams, and many of the ladies who befriended her were those she had been helped by in her visions.13

Sanborn also wrote that on dangerous missions during the mid-1850s, after a reward had been offered for her capture, “she several times was on the point of being taken, but always escaped by her quick wit, or by ‘warnings’ from Heaven…”14 These warnings, he wrote, came to her often as a fluttering in her heart. “She says she inherited this power, that her father could always predict the weather, and that he foretold the Mexican war.”15

Bradford, the first individual to attempt a book-length biography of Tubman, was of a similar mind to Sanborn. Her two books on Tubman—a hastily composed set of personal reminiscences and letters published in 1869 as Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman and then a more polished but also more sanitized version published in 1886 as Harriet: The Moses of Her People—relate several of Tubman’s claimed “dreams and visions.” But like Sanborn, Bradford was quick to signal the delicacy of the subject of Tubman’s supernormal experiences and her own semi-ambivalence toward them.16 She claims she limited the stories in her book to those that could be verified by others or that she had witnessed firsthand, for fear of bringing too much discredit on her subject.17

Bradford reported witnessing episodes of religious rapture in Tubman, as well as the apparent facility with out-of-body travel that Sanborn mentioned: “When the turns of somnolence come upon Harriet, her ‘spirit,’ as she says, goes away from her body, and visits other scenes and places, and if she ever really sees them afterwards they are perfectly familiar to her and she can find her way about alone.”18

In her first book, Bradford reproduces an account related to her in a letter by Wilmington, Delaware, abolitionist Thomas Garrett, describing what has become one of Tubman’s most famous exploits as a conductor on the Underground Railroad: leading a small group including two “stout men” to freedom. (Larson suggests this episode may have occurred in the spring of 1856.) Garrett relates that about 30 miles south of Wilmington,

God told her to stop, which she did; and then asked him what she must do. He told her to leave the road, and turn to the left; she obeyed, and soon came to a small stream of tide water; there was no boat, no bridge; she again inquired of her Guide what she was to do. She was told to go through.19

Despite the cold—it was March—Tubman had complete confidence in her divine guide, so she began wading across, the water rising as high as her armpits. The men refused to follow her until they saw her safely reach the far shore but then entered the frigid water. The group then had to ford a second stream before they found the cabin of a Black family who gave them shelter and dried their clothes. Tubman left them some undergarments in payment, but contracted a respiratory ailment from the ordeal—she was barely able to speak when she and her party arrived in Wilmington two days later. Garrett adds “the strange part of the story”: that Tubman and party discovered when they came out of hiding that the fugitives’ master had put up reward posters for them at a nearby train station, suggesting by implication that Tubman’s unexpected course of action may indeed have saved them from being caught.20 Bradford retold this story in her second biography and added that she had also heard the story from Tubman herself on multiple occasions.21

Another oft-retold story first reported by Bradford is associated with one of those allegedly accurate somatic presentiments Sanborn mentioned: Tubman became “much troubled in spirit about her three brothers, feeling sure that some great evil was impending over their heads.”22 So she enlisted a friend to write a letter for her to a literate free Black man in the area where her brothers lived, named Jacob Jackson, indicating in code that her brothers should be ready for her arrival. The message evaded detection by inspectors who were reading Jackson’s mail, and her arrival came, she said, just in the nick of time:

When Harriet arrived there, it was the day before Christmas, and she found her three brothers, who had attempted to escape, were advertised to be sold on Christmas day to the highest bidder, to go down to the cotton and rice fields with the chain gang…. When the holidays were over, and the men came for the three brothers to sell them, they could not be found.23

There is no way to verify the accuracy of Tubman’s claimed presentiments—for instance that she knew in advance the urgency of going to rescue her brothers, or that God’s voice directed her to ford a stream because pursuers were close to catching them. Nor is there any way to verify the claims that Tubman had actually seen her future refuges and helpers in her dreams or out-of-body travels—which would make those experiences “veridical” in the language of parapsychologists. But slaves she had helped to freedom witnessed these kinds of marvels firsthand and held her in awe because of them.

When Black novelist and historian William Wells Brown interviewed former slaves in Canada in 1860, they told him that “Moses has the charm”—a kind of superhuman charisma. “The whites can’t catch Moses, cause you see she’s born with the charm. The Lord has given Moses the power.”24 Brown also wrote that Black soldiers in camps Tubman visited during the Civil War “would have died for this woman, for they believed that she had a charmed life.”25 Tubman herself believed this, saying that the charm gave her courage, “nerved her up” in adversity and did the same for her followers. In her totally confident hands, they felt safe.

There seemed to be more to this quality than just courage. Sanborn, trying to explain Tubman’s charm, attributed it to her intelligence and her heavenly warnings. Thomas Garrett, in his letter to Bradford, attributed it to her overriding trust and confidence in God, her guide:

[I]n truth I never met with any person, of any color, who had more confidence in the voice of God, as spoken direct to her soul. She has frequently told me that she talked with God, and he talked with her every day of her life, and she has declared to me that she felt no more fear of being arrested by her former master, or any other person, when in his immediate neighborhood, than she did in the State of New York, or Canada, for she said she never ventured [anywhere except] where God sent her, and her faith in a Supreme Power truly was great.26

Although less colorful and dramatic than the alleged presentiments guiding Tubman in her rescue missions, friends and associates reported other remarkable, seemingly “clairvoyant” episodes centered on specific sums of money being sent or set aside for her—first to finance her missions and then, after the Civil War, to support the poor Black people she boarded at her home in Auburn, New York. For instance, Garrett recounted a visit in which she said, “God tells me you have money for me.” “Well!,” he exclaimed, “how much does thee want?” “About twenty three dollars,” Tubman answered. Garret writes that he “then gave her twenty-four dollars and some odd cents, the net proceeds of five pounds sterling, received through Eliza Wigham, of Scotland, for her.”27 This was the first time Tubman had come to Garrett for money, and the first time that he actually had received a donation for her, so the timing as well as the precision are interesting.

Tubman called on Garrett again a year later, saying God had told her he once more had “some money for her, but not so much as before.” The abolitionist had indeed, just a few days prior, received the equivalent of one pound and ten shillings sent from Europe for her cause. “To say the least,” Garrett noted, “there was something remarkable in these facts, whether clairvoyance, or the divine impression on her mind from the source of all power, I cannot tell; but certain it was she had a guide within herself other than the written word, for she never had any education.”28

Bradford reported that, on another occasion, Tubman “received an intimation in some mysterious or supernatural way” that her parents needed rescue and “asked the Lord where she should go for the money to enable her to go for them.” In answer, she was “directed to the office of a certain gentleman, a friend of the slaves, in New York,” whom she asked for $20, explaining that the Lord had sent her. Incredulous and having no money for her, the gentleman said, “Well I guess the Lord’s mistaken this time.” Undeterred, Tubman sat and slept the whole day, arousing the attention of visitors to the office, who shared stories of her exploits. “At all events she came to full consciousness, at last, to find herself the happy possessor of sixty dollars, the contribution of these strangers. She went on her way rejoicing to bring her old parents from the land of bondage.”29

In a revised edition of her second biography of Tubman, Bradford also recalled an episode some years later, when she forwarded a $7 donation for Tubman to a prominent woman physician in Auburn, New York, who was acting as Tubman’s treasurer. Bradford later received a letter from the physician saying Tubman had previously come to her asking for a $7 loan to pay her bills and promising she could repay the debt the following Tuesday. Teasing her, the physician had asked her how she could trust that the debt would be repaid on Tuesday, to which Tubman reiterated her promise, saying “I can’t just tell you how.” The physician received Bradford’s package with the $7 for Tubman on the Tuesday in question. “Others thought this strange, but there was nothing strange about it to her.”30

Ghosting John Brown

Besides Tubman’s oft-quoted dream of Emancipation that caused her to rejoice three years ahead of the actual event, the best-known of Tubman’s dreams, and the only one recorded in much detail, is a recurring dream that she told Sanborn had preceded her first meeting with John Brown in St. Catharines, Ontario, in April 1858. Brown, it must be noted, was already in awe of Tubman, calling her “the General,” and desperately hoped for the seasoned guerrilla’s participation in the raid he had been planning—for several years by that point—to conduct on Harper’s Ferry.31 Sanborn writes that, in Tubman’s dreams,

She thought she was in “a wilderness sort of place, all full of rocks and bushes,” when she saw a serpent raise its head among the rocks, and as it did so, it became the head of an old man with a long white beard, gazing at her “wishful like, just as if he were going to speak to me,” and then two other heads rose up beside him, younger than he,—and as she stood looking at them, and wondering what they could want with her, a great crowd of men rushed in and struck down the younger heads, and then the head of the old man, still looking at her so “wishful.” This dream she had again and again, and could not interpret it; but, when she met Captain Brown, shortly after, behold, he was the very image of the head she had seen. But still she could not make out what her dream signified,till the news came to her of the tragedy of Harper’s Ferry, and then she knew the two other heads were his two sons.32

Brown’s plan was to lead an army of volunteers, including fugitive slaves, to take over the armory in Harper’s Ferry. They were going to distribute the weapons to the local slaves, enabling them to rise against the slaveowners. The idea was to deplete Virginia of its slaves, county by county, in a growing movement that would ultimately shatter the slave economy throughout the South. After a year’s postponement, Brown finally led his crusade on October 16, 1859, with the help of only 21 men—far fewer than what he had hoped for.

According to Sanborn, Tubman was in New York at the time and “felt her usual warning that something was wrong—she could not tell what. Finally she told her hostess that it must be Captain Brown who was in trouble, and that they should soon hear bad news from him. The next day’s newspaper brought tidings of what had happened.”33 The tiny force had successfully captured the armory and cut off telegraph communication to the outside world; but a railroad carried news to a neighboring town and a militia was summoned to put down the insurrection. One of Brown’s participating sons escaped, but two were killed. Brown himself was captured, tried, found guilty, and executed by hanging on December 2.

One of the big question marks in Tubman’s life centers on her absence at that ill-fated raid. In her initial meetings with Brown and his followers in April 1858, she was enthusiastic and proceeded to help him recruit volunteers among former slaves in Ontario. She met with him again as late as May 1859. Yet strangely, Tubman was nowhere to be found in the summer and fall of that year as the planned action drew near. All efforts of Brown’s followers to locate her failed. Sanborn suggested that perhaps she fell sick or had to attend her sick parents. But it has occurred to some historians like Larson that Tubman may have realized the flaws in Brown’s plan and feigned being sick to avoid his disapproval—“ghosting” him, as we would now say.

I’m not aware of historians drawing a connection between Tubman’s absence at Harper’s Ferry and her famous dream about Brown, but it strikes me as an obvious piece of the puzzle. Tubman was a conscious shaper of her own story, and that would have included her divulgences to her white biographers like Sanborn about her dreams and how she interpreted them—or in this case, didn’t interpret them. Assuming the dream account itself is true and faithfully told, I find it implausible that someone as attuned to her dreamlife as Tubman was would be able to tell that the serpent in her dream was Brown upon meeting him but only recognize the ominous symbolism (the serpent-heads being struck down) after the failed raid. Was it the dream that kept her away? Might it at least have confirmed a conscious inkling that, however noble Brown’s intentions in making open war on Southern slavery, his crusade was doomed to end in failure?34

There is no way of knowing, but I believe circumstances do point to the dream-story’s authenticity. Why invent such an obviously dark oneiric prophecy about her friend and ally Brown that she obviously did not act on (i.e., she didn’t warn or dissuade him). Relating it to Sanborn as a dream that she just didn’t understand the meaning of until too late seems like a judicious compromise. Interestingly, and I suspect also relevantly, Sanborn reported that Tubman retained a practically religious devotion to Brown after his death, saying that it was God who died at the gallows that day, not a mere man. A Freudian, attuned to how people often overcompensate for unconscious guilt feelings, might have something to say about that devotion.

Other precognitive dreams of Tubman were reported by her friends after the Civil War. For instance, in late January 1884, Tubman visited friend and fellow suffragist Eliza Wright Osborne and told her host some “mysterious dreams and thoughts that had come to her” that were troubling, including a dream about a week before in which she “saw so many people drowning and some burning up.” Osborne showed her a newspaper from the time of the dream, reporting on the wreck of the steamer City of Columbus off Martha’s Vineyard, in which more than 100 lives were lost—among them, many women and children. Tubman said she “had not heard of it.”35

In the revised edition of her second Tubman biography, issued in 1901, Bradford included several pages of new material based in part on recent interviews with her subject. There were additional dreams, including one about a terrible earthquake:

She woke from a sleep one day in great agitation, and ran to the houses of her colored neighbors, exclaiming that “a dreadful thing was happening somewhere, the ground was opening, and the houses were falling in, and the people being killed faster than they was in the war faster than they was in the war.” At that very time, or near it, an earthquake was occurring in the northern part of South America, for the telegram came that day, though why a vision of it should be sent to Harriet no one can divine.36

There is no date given for this dream or the earthquake, but it was probably the devastating San Narciso earthquake that caused fissures in the ground, building collapses, and many deaths in towns near the Venezuelan coastal capital of Caracas in 1900.

Bradford also reported how Tubman learned in a dream of the unexpected death of young Fanny Seward, a friend of hers and the daughter of Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William H. Seward:

Sitting in her house one day, deep sleep fell upon her, and in a dream or vision she saw a chariot in the air, going south, and empty, but soon it returned, and lying in it, cold and stiff, was the body of a young lady of whom Harriet was very fond, whose home was in Auburn, but who had gone to Washington with her father, a distinguished officer of the Government there. The shock roused Harriet from her sleep, and she ran into Auburn, to the house of her minister, crying out: “Oh, Miss Fanny is dead!” and the news had just been received.37

Fanny Seward died in October 1866, so this story was likely based on notes from interviews Bradford had conducted years earlier, for her first biography of Tubman.38 She may have left it out of that book because of its uncomfortably supernatural-sounding subject matter.

Explaining Away

Unsurprisingly, given the variable nature of the evidence and the fact that it all dates from a fading, sepia-toned past, skepticism still clouds the reports of Tubman’s premonitory dreams and presentiments. While a few of the above stories have found their way (sometimes embellished) into children’s books or writings and videos on dreams or the paranormal,39 serious biographers have minimized or wholly ignored this dimension of Tubman. At best, it is considered an unverifiable and unexaminable “subjective side” of her story, as historian Milton C. Sernett puts it—part of Tubman’s “non-white religious self.”40

What was that religious self? Tubman’s background was probably a mélange of many faith traditions and practices. The Brodesses were Methodists, and Tubman and her fellow slaves were forced to attend Methodist services. But there may have also been Baptist, Episcopal, and Catholic influences (Tubman fasted on Fridays, for instance—a mainly Catholic practice), as well as influences from increasingly popular Black evangelical churches, which subversively preached the promise of deliverance from enslavement. To these various flavors of Christianity must probably be added West African beliefs and traditions, which included beliefs in magic and divination and the reality of prophetic dreams.41 There is reason to think that at least one of Tubman’s grandparents was brought on a slave ship from what is now Ghana, on the Gold Coast; and as a child she was told that her heritage was Asante, one of the main ethnic groups of that region. Whatever went into the mix, Tubman’s was a vivid and daily—or constant—lived experience of a real and vital connection to a higher power. Biographer Jean Humez writes that “Tubman’s God emerges … as an approachable partner and unfailing support for those who were righting wrongs. God was her name for the source of visionary guidance for her antislavery action. Prayer enabled her to tap directly into the source of such guidance.”42

Nor would Tubman’s earliest biographers have had much besides a religious idiom in which to explain her experiences—indeed a much narrower Christian idiom—and this accounts for some of the hesitation shown toward her stories. Most white Christians of the time believed that God heard their prayers, but the idea that God talked back was not yet the mainstream belief that it became for white evangelicals in the next century.43 A Presbyterian, Bradford herself was uncomfortable with the idea of Tubman actually getting a reply when she talked to God, as in the episode with the cold river-crossing.44

Especially in the latter part of the 19th century, there were alternative framings that writers could have drawn on, had they been cognizant of them. The new religious movement Spiritualism had already been flourishing in the western half of New York state, where Tubman settled after the Civil War. Many abolitionists embraced this trend, and it may have had some effect on the positive acceptance of Tubman’s story in these circles, if not among her biographers.45 Soon, the world of science and technology would provide new metaphors that eventually helped frame things like prophetic dreams and visions in a less spiritual or religious way. Drawing on the recent innovation of the telegraph, English classicist Frederic W. H. Myers coined the term “telepathy” in 1882 as a theory to explain what we would now call psychic or ESP experiences, including the kinds of premonitory visions and dreams that various friends and biographers of Tubman described. But the ideas and findings of nascent psychical research don’t seem to have influenced Tubman’s biographers any more than Spiritualism did.

The sort of somatic, “heartfluttering” warnings Tubman reported . . . are also a common feature, anecdotally, in the lives of psychics; the military is even known to have funded research on “Spidey sense.”

In the 20th century, mainstream academic or scientific culture continued to marginalize psychical research, even after J. B. Rhine and Louisa Rhine introduced more rigorous scientific methods in studying ESP at Duke University in the 1930s. The persistent gap between the robust support for ESP generated by parapsychologists and skepticism by mainstream scientists is well-known. The same skepticism—or really, ignorance of the whole topic—pervades the humanities as well. Thus it is unsurprising that modern historians have mostly failed to even consider Tubman’s experiences as ESP evidence.

The problem is compounded by Tubman’s status as a progressive icon. After Bradford, the next person to write a major biography on Tubman was a leftist journalist named Earl Conrad, who went to great lengths to minimize the spiritual and supernatural dimension of Tubman’s story. Conrad was keen to portray Tubman as an effective radical and a revolutionary—perhaps the greatest-ever American hero—but his Marxist materialist worldview could not assimilate her mysticism. When he was researching her life in the 1930s, he wrote to psychiatric hospitals for insight, describing her narcolepsy, hallucinations, talking to God, and belief in prophetic dreams and omens (noting that she was regarded by those who knew her as “touched in the head”). He received replies from physicians who variously attributed these things to her traumatic experiences as a slave, to hysteria, and to the head injury.46 Since there was no consensus of professional medical opinion, he ultimately left the matter of his subject’s visionary experiences out of his 1943 biography, Harriet Tubman.47

Alice Brickler, a daughter of one of Tubman’s nieces, conducted a cordial but disputatious correspondence with Conrad about this aspect of her great aunt while he was researching his book. Conrad had asserted in a letter that Tubman’s visions and dreams were “by no means the most important thing” about her, but Brickler forcefully countered that her religious life should not be omitted:

I may be wrong but I believe that every age, every country and every race, especially during the darkest history, has had its unusual Souls who were in touch with some mysterious central originating Force, a comprehensive stupendous Unity for which we have no adequate name. Aunt Harriet was one of those unusual souls. Her religion, her dreams or visions were so bond together that nobody, and I certainly should not attempt it, could separate them.48

Although not religious herself, Brickler added that as “a member of an oppressed race” her Aunt Harriet needed “the inspiration of the mystic as well as sagacity,” and that “It was her dreams which saved her life often . . . and it was her superhuman courage and beliefs which gave her the power to accomplish what she had undertaken.”49 Conrad, who could not imagine a religious worldview that was not an opium of the masses, was not to be swayed. He replied to Brickler that “God is a piece of heavy artillery, employed by the rich to keep the poor content, satisfied, unrebellious, unmoving.”50 And that was that.

A neurobiological explanation for Tubman’s experiences has served as an escape hatch for other biographers. In her comprehensive and otherwise excellent 2003 biography, Bound for the Promised Land, Larson attributed Tubman’s sleeping spells, visions, and religiosity to temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), a neurological disorder first described in the mid-1970s (originally as Geschwind Syndrome).51 Powerful religious visions, disembodied voices, alternating hyperactivity and fatigue, out-of-body experiences, and trance states are famous symptoms of this condition, and they sometimes arise after severe head injury.

Given how closely Tubman’s behavior matches TLE symptomatology, it is certainly plausible that she had it. But we must be careful: Neuroscience is often used as a cudgel against paranormal claims. Any diagnosis of brain injury or disease tends to carry the implication that, whatever the individual’s own convictions, their experiences are not “real.” In writings on dream research, one will often see some version of the trope: “dreams were once thought to carry omens of the future, but then science showed that they could be explained as phenomena of the brain.” The both-and possibility (which I make a case for in my work52) remains unconsidered. To acknowledge that Tubman may have had TLE, in other words, says nothing about the possible veridicality of the dreams and visions that her condition might have produced or facilitated.

Also, people can be religious and believe in their dreams and visions without TLE. Those things were very much features of Black culture at the time, and after. As Sernett writes, “What Conrad missed and Bradford sought to domesticate belongs to the prophetic and visionary strand African American religion sometimes associated with the belief that certain individuals are born with unusual seer-like powers.”53 But the fact that a folkloric belief in psychic phenomena was part of Tubman’s cultural milieu again lets biographers wash their hands of the precognitive claims—they can chalk it up to her (implicitly superstitious) “non-white religious self.” Once more, there’s a both-and that falls through the cracks. Abundant robust evidence suggests that, on the subject of what we can loosely call prophecy, folklore—including African religious beliefs—is far closer to the reality than mainstream scientific psychology currently is.

Super + Natural

Decades of findings from multiple laboratories now support precognition in various forms. A famous meta-analysis of forced-choice (Zener card) precognition experiments conducted over several decades revealed astronomically high support for precognition.54 Using remote viewing-type tasks, researchers at Princeton’s PEAR lab gathered significant evidence that participants can draw or describe targets that haven’t been selected yet with greater-than-chance accuracy.55 Predictive physiological responses, or “presponses,” to stimuli have garnered considerable research attention since pioneering studies by Dean Radin in the mid-1990s, and meta-analyses of this body of research also show overwhelming statistical support.56 The sort of somatic, “heart-fluttering” warnings Tubman reported to Sanborn are also a common feature, anecdotally, in the lives of psychics; the military is even known to have funded research on “Spidey sense.”57 And there is growing evidence for behavioral presponses as well: Findings from Cornell psychologist Daryl Bem’s famous “Feeling the Future” series of experiments published in 2011 have been replicated by multiple labs.58

Precognition/presentiment often anecdotally manifests as auditory “hallucination.” A psychic and ESP researcher in the mid-20th century, Rosalind Heywood, reported receiving what she called “orders” from a disembodied voice that only made sense in light of information she would learn later, typically after following the voice’s strange instructions.59 One of the most famous living psychics, the remote viewer Joe McMoneagle, reported an inner voice guiding him away from danger during his time in Vietnam.60 Trance medium Jess Taylor describes receiving “telepathic” instruction as though via an earphone that discretely directs her to places where she will find a person in need of aid and then instruction in how to provide that aid—information that, she claims, proves accurate.61

Proneness to out-of-body experiences is another commonly reported characteristic of psychics, both those with a natural untrained ability and those who have been trained in modern methods like remote viewing. Three of the most studied and storied psychics of the famous Star Gate psychic spying program and the research at Stanford Research Institute that led to it—McMoneagle, Ingo Swann, and Pat Price—reported a facility with traveling out of body; Swann and Price, who developed this ability as part of their Scientology training, both reported obtaining psychic information in such a state.62 An argument can be made (controversially) that what seem like “out of body” experiences are really vivid or video-quality previews of in-body experiences later during waking life.63

The “charm” attributed to Tubman is a familiar part of battlefield folklore, going by different names. Some charismatic individuals seem magically protected from danger and emanate a kind of calming authority. Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now is a fictitious version of this archetype, but a real one might be the Australian photographer and explorer Sir George Hubert Wilkins. During World War I, Wilkins was seen striding fearlessly across battlefields with his camera, bullets whizzing by him or harmlessly bouncing off his coat. He felt protected by a supernatural or supernormal force. Like Tubman, he described what we would now call extrasensory presentiments and warnings—a sort of Spidey sense, which baffled and inspired his companions and later saw him through numerous perils as a polar explorer.64

Precognitive dreams are the most common paranormal experience, reported by a large percentage of the population and accepted as a normal feature of dreaming by most non-Western cultures, including African cultures like the Asante that influenced slave folklore and beliefs.65 As is quite typical for those who report such dreams, Tubman’s dreams sometimes related to events that were soon to be reported in the news or that she would soon be told of, even if they had already happened. These kinds of uncanny yet “random” and often news associated dreams are sometimes called “Dunne dreams,” after the precognitive dreamwork pioneer J. W. Dunne, whose 1927 book An Experiment with Time is one of the most important books ever written on the subject.66 Dreams are notoriously hard to study scientifically, however, and this is doubly the case for precognitive dreams. They typically occur spontaneously, and with limited exceptions, experiencers typically aren’t aware of having had a precognitive dream until the precognized event comes to pass. Skeptics thus dismiss precognitive dream reports as hindsight memory distortion; yet when dreamers do carefully record and date their dreams, the records can frequently be shown to match later events and learning experiences, just as Dunne claimed. As I and a growing number of researchers in this field have shown, there is more than ample evidence that dream precognition not only is real but in fact is common. I argue it is basic to dreaming’s function.67

A detail of Tubman’s life that is consistent with the biographies of some psychics is the head injury she received in her early teens. The only Tubman biographer to take the psychic claims seriously, James A. McGowan, argued that it was this event that activated her abilities, noting that some contemporary psychics similarly attributed their powers to head injuries— Dutch psychic Peter Hurkos being a famous example.68 Other physical traumas like lightning strikes or fevers, as well as psychological traumas including histories of abuse, are also common in the biographies of psychics and experiencers of the paranormal, as they are, notably, in spiritual workers like shamans throughout the world.69

Some writers have talked about physical as well as psychological trauma as “unlocking” (or in Whitley Strieber’s phrase, “cracking open”70) supernormal capacities and perceptions. It is an intuitively compelling metaphor, but it may be possible to specify some more precise psychological mechanisms—most notably, dissociation. Out-of-body experiences may be triggered as a way of escaping traumas when they are occurring. With repeated traumatic experience, that dissociation can become habitual or second nature. Unsurprisingly, out-of-body “flights to freedom” were a common slave experience;71 this is easily attributed, reductively, to cultural tradition and, implicitly at least, a kind of Freudian wish-fulfillment, but trauma must be considered as a factor.72 Anecdotally at least, trauma induced dissociative experiences may contain veridical precognitive information similar to that available in dreams.73

Another circumstance that can produce waking and semi-waking altered states is attempting to stay awake despite extreme fatigue. Although writers on Tubman’s dreams have given it less attention than the head injury, the terrible period “Minty” spent as a nurse for the cruel Miss Susan is potentially just as relevant. To keep Miss Susan’s “cross, sick child” from rousing her mother, Minty had to fight to remain conscious and would be promptly whipped about the face and neck when she (inevitably) did fall asleep. (Bradford said that the scars from those punishments, like the head wound, were still visible decades later.) The desperate effort to remain awake despite overwhelming sleepiness readily generates hypnagogic experiences—both visual and auditory—as well as more profound perceptual distortions and out-of-body experiences. So does constantly interrupted sleep from tending infants.74 What is more, dreamworkers may find that hypnagogic images and voices may relate to later or imminent experiences as much or more even than standard dreams.75 Whatever the added effect of the later head injury in inducing her “sleeps,” I think it is important to consider that 8-year-old Araminta Ross’s stint with Miss Susan could have been what effectively “trained” the future Harriet Tubman in accessing, abiding in, and perhaps attending to these potentially precognogenic liminal-dream states.76

I also consider Tubman’s famous prayer for the death of her master Edward Brodess to be an item potentially added to the list of evidence for her specifically precognitive (and not generalized “psi”) abilities. She told Bradford that she had regularly prayed for Brodess to repent of his wickedness, but that upon hearing plans to sell her and her siblings away, she changed her prayer: “First of March I began to pray, ‘Oh, Lord, if you aren’t ever going to change that man’s heart, kill him, Lord, and take him out of the way.”77 Brodess died just over a week later, on March 9, 1849. Parapsychologists interested in PK and the “power of prayer” will certainly disagree here, but I’ve argued elsewhere that conscious intentions or decisions, especially of highly intuitive people, may be precognition misrecognized.78 Individuals with a strong and perhaps overdeveloped sense of self-efficacy—sometimes called “internal locus of control”—may overinterpret their own intentions as directly causative over events or causative via the mediation of some reliably compliant supernatural power.79 Such a sense of self-efficacy (via God) certainly applies to Tubman.

Referring to the role of unrecognized or misrecognized precognition in producing expectation effects in laboratory research, Edwin May describes “decision augmentation”: precognitively making choices (e.g., in sorting of test and control subjects or in experiment timing) that will lead to the desired result.80 Tubman’s change of her prayer just a week before Brodess’s death could have been decision augmentation in more or less this sense. The same framing potentially applies to many of Tubman’s decisions, such as the timing of her rescue missions that (she claimed) came often in the nick of time.

The bottom line: For those with awareness of the kinds of phenomena reported in parapsychology—some with strong laboratory support, others necessarily more anecdotal—the claims made by and about Tubman fit a familiar pattern. Nevertheless, with Conrad, Larson, and other academic biographers, we find ourselves in the typically ossified and brittle discursive universe that Rice University Religion Historian Jeffrey J. Kripal has noted characterizes the humanities around the most remarkable, “super” human experiences. First of all, there is an inability or unwillingness to confront challenging topics by “making the cut”—that is, to separate ostensible paranormal experiences from supernatural explanations given them by experiencers themselves and, as in this case, their biographers.81 We need not see any account of Tubman’s dreams and visions and answered prayers as a “biography of the Supreme Being,” as Conrad reductively and obstinately put it in his correspondence with Brickler.82 Humez’s remark that God was Tubman’s word for the visionary source of her antislavery action is what we need to bear in mind. It is perfectly possible to set aside or bracket the question of who was talking to Tubman—God, her own future self, or something else entirely while acknowledging both the importance of those inner dialogues to her life and achievements and, more to the point, the possible veridicality of the information that inner voice provided. Her experiences could be both “super” and “natural,” in other words.83

Toward a Multidimensional Harriet Tubman

This year is (probably) the bicentennial of the birth of Araminta Ross in a Maryland slave cabin. At this historical distance, a complete and clear picture of the woman she became is difficult to assemble, and likely we will never have it. Her slave-liberating actions before the Civil War and her military missions during it were conducted with great secrecy; and because she could not write her own story, we are forced to extract it from the written narratives of others—individuals who, however well meaning, had their own distinct biases. Tubman was biased too. Humez stresses that even if she could not write, she was an active shaper of her own narrative via those abolitionist and suffragist allies helping her tell it. Consequently, Harriet Tubman remains an ambiguous figure, with many seemingly hard-tointegrate facets, a kind of Rorschach blot for later writers.

I am sensitive to the fact that, outside the narrow confines of discourses of the paranormal and parapsychology, psychic experiences are sometimes used to invalidate those who express or believe in them as being naïve or uncritical. So, is “Harriet Tubman, Precog” ready for prime time? Only if, in telling this part of her story, we do not lose sight of the other, equally important and timely Harriet Tubman stories, of which there are a growing number. “Harriet Tubman, Astronomer” is one of them. Her name has recently been put forward to replace that of the homophobic NASA administrator James Webb for the lately deployed deep-space telescope, as she famously used her knowledge of the stars to tell time and guide her in her flight to freedom; she was also a witness to one of the most spectacular meteor showers ever recorded, in 1833.84

“Harriet Tubman, Amazon,” is another important story being (re)told. A rousing 2015 “re-biography” by feminist historian Butch Lee attempts to restore Tubman’s political acuity and revolutionary militancy that somehow get lost in most of the books about her life. Long before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter, Tubman was helping current and former slaves wage a successful war on slavery; she wasn’t just rescuing people on some humanitarian Red Cross mission. And like Conrad before her, Lee leaves the dreams and talking-to-God completely unmentioned. The reasons are obvious: Lee asserts that most white-written histories make Tubman out to be an anomaly, something exceptional and superhuman, which ultimately minimizes her political thoughtfulness, her military prowess, and her professionalism—qualities shared by many equally committed Black people of that era. Lee is right. Somehow, the hard-as-nails, coarse-mouthed guerrilla, who would threaten hesitant fugitives with a gun to their head, saying “Go on or die,” magically transforms in some biographers’ and artists’ eyes into a nonviolent do-gooder, a Florence Nightingale-type and a “visionary.” I admit that I too succumbed to this beguilement when I first began researching Tubman a few years ago, tending to just skip over the violent, darker stuff, in search of that nurturing, superhuman rescuer and dreamer.

Bradford’s well-intentioned and still widely read biographies, especially the sanitized 1886 Harriet: The Moses of Her People—written at Tubman’s request, to provide needed revenue or her boarding of poor Blacks in Auburn—unfortunately perpetuate this one-sided, charity working view of Tubman. Calculated to appeal to white readers in a wounded nation still trying to heal from the North-South divide, Bradford minimized the horrors of Tubman’s slave experiences and softened the rougher edges of her personality.85 And by using dialect (“de” instead of “the,” etc., when quoting her), the effect was to compromise her subject’s dignity and intelligence. The ironic result is that Tubman’s favorite disguise—the harmless, possibly touched-in-the-head, God-praising old Black woman—still exerts its effect on many white Americans more than a century and a half later.

All of which is to say that the psychic Harriet Tubman, with visions and dreams and conversations with a higher power, must remain properly framed in the context of Tubman the freedom fighter, Tubman the activist, Tubman the suffragist, and yes, Tubman the Amazon. Somehow integrating all these sides of her would create a more multidimensional picture than any of those yet written: of a Black woman who contributed in significant ways to the most important social struggles of her time and (not “yet”) whose intuitive or psychic abilities played an important role in those efforts. That she was some kind of psychic superspy scanning the paths ahead with nonlocal consciousness is perhaps debatable. (I think that appealing picture is debatable with Cold War psychic spies too.86) But that she exercised precognitive intuition throughout her life and work, and that her open communication with the divine gave her an aura that galvanized and strengthened herself and others during adversity, seem hard to question. In fact, that supernatural-seeming charm may, in the end, be the most crucial part of the psychic picture I have tried to paint. The fact that Tubman’s story has reminded so many people of Joan of Arc is no counterargument to it. If anything, it should prompt us to make the cut and consider the both-and possibility: that prophetic dreams and the charm that comes from a divine mandate could be a real pattern in the lives of charismatic freedom fighters, whenever and wherever they appear. Super and natural.

and wherever they appear. Super and natural. If I seduced you at the beginning of this article with the visionary Tubman and her nice dream foretelling Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, I would leave readers with another image that seems to encapsulate not only her commando skills but, at the same time, her immense humor and her charm (in its more mundane sense). Alice Brickler recalled a childhood visit with her mother to the elderly Tubman’s Auburn home:

[Aunt Harriet] and Mother were talking as they sat in the yard. Tiring of their conversation, I wandere off in the tall grasses to pick wild flowers. Suddenly I became aware of something moving toward me through the grass. So smoothly did it glide and with so little noise, I was frightened! Then reason conquered fear and I knew it was Aunt Harriet, flat on her stomach and with only the use of her arms and serpentine movements of her body, gliding smoothly along. Mother helped her back to her chair and they laughed. Aunt Harriet then told me that that was the way she had gone by many a sentinel during the war.87

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a presentation given in December 2021 at the first Black Superhumanism symposium at Esalen’s Center for Theory and Research. I thank the organizers, Dr. Stephen Finley and Dr. Biko Mandela Gray, for inviting me and for giving me the opportunity to present my still-forming thoughts on Tubman. I also thank the seminar participants for extremely valuable feedback and discussion, which contributed greatly to this article.

ERIC WARGO is a researcher on precognition, dreams, and the paranormal. He has a Ph.D. in anthropology from Emory University and is the author of two books: Time Loops and Precognitive Dreamwork and the Long Self. He is currently working on a book about precognition and creativity. He also writes about parapsychology, time travel, and consciousness at his blog, The Nightshirt. Eric lives in Fairfax, Virginia, and can be reached on Twitter @thenightshirt.

ENDNOTES

1 It was the convention in the 19th century to quote Black voices in dialect—“de” instead “the,” “dere” instead of “there,” etc. Throughout this article, I am removing the dialect in direct quotes related by Tubman’s early biographers, such as this vignette recounted in Sarah H. Bradford’s 1886 book Harriet: The Moses of Her People.

2 Humez, Jean M. (2003). Harriet Tubman: The Life and Life Stories. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press.

3 An invaluable guide to the uncertain and sometimes contradictory landscape of Tubman historiography is Milton C. Sernett’s 2007 Harriet Tubman: Myth, Memory, and History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

4 Unless otherwise noted, I’m taking Tubman’s biographical details from Kate Clifford Larson’s comprehensive 2003 biography, Bound for the Promised Land (New York: Random House). Other sources have put her birth in 1820.

5 Bradford, Sarah H. (2018[1869]). Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. [np].

6 In Harriet’s absence, John Tubman married another woman. Although it has often been portrayed as a painful blow to Harriet when she returned for John and found him remarried, she used the opportunity to rescue several other slaves, and later in life, she recounted this episode, and John’s unfaithfulness, with much amusement.

7 Sernett (2007) argues that the evidence points to 9 trips and from 60 to 80 people liberated. Humez (2003) arrives at 11 or 12 trips and 66–77 people liberated.

8 Lee, Butch. (2015.) “The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman.” In Jailbreak Out of History. Montreal, Canada: Kersplebedeb Publishing.

9 Sernett (2007) disputes the appellation “General” often given to Tubman as a result of her Civil War exploits, noting that Tubman herself acknowledged in a letter that Montgomery actually led the raid, even if she did the advance intelligence work and planning.

10 Bradford, 1869.

11 Sanborn’s 1883 Commonwealth article, partly reproduced In Bradford, 1869, 39.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid., 40.

16 Sernett, 2007.

17 Bradford, 1869, 28.

18 Ibid.

19 In Bradford, 1869, 26.

20 Ibid. This story was embellished, as well as conflated with what was probably a separate mission, the rescue of Josiah Bailey, in Ann Petry’s 1955 young-adult biography, Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad (New York: HarperCollins Publishers). Popular dreamwork teacher Robert Moss, drawing on Petry’s account of Tubman’s precognitive dreams in his 2000 book Dreaming True (New York: Pocket Books), reproduced Petry’s inaccuracies, for instance saying that Tubman’s guidance in this instance came in a dream during one of her “sleeps.” The guidance in this case came in a waking state. Petry also writes that the fugitives returned to the shore of the river where they had first crossed and found trampled grass and cigar butts indicating that the search party had been there, an embellishment of Garrett’s detail about the posted reward at a nearby train station.

21 Bradford, 1886.

22 Bradford, 1869, 29

23 Bradford, 1869, 29–31

24 In Sernett, 2007, 134

25 In Sernett, 2007, 134

26 In Bradford, 1869, 26.

27 In Bradford, 1869, 26–7.

28 Bradford, 1869, 27.

29 Bradford, 1869, 50 (italics in original).

30 Bradford, Sarah H. (1901). Harriet: The Moses of Her People, revised edition; https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9999/old/8htub10.txt

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.